Dennis Cliff first spoke about his experiences to me in 2010. He was pleased that someone was interested in the story of his RAF service but was hesitant about it being published. Dennis never applied for the WW2 medals to which he was entitled. However, more recently, he was happy to receive the Légion d’Honneur medal offered to surviving D-Day veterans. Typically, he didn’t want to be presented with it, and it was sent to him. The last time I saw Dennis, he told me that perhaps I could publish his story, “When I’m gone”. Dennis passed away on 12th March 2022, aged 98.

Mike Fenton (Editor)

Here is his story, slightly abridged to focus on his beach unit experience.

I was born in Rotherham, went to Rotherham Grammar School and I lived in Rotherham until 1957. I volunteered for the Fleet Air Arm in early 1942, because I wanted to fly, and I wanted to fly with the Fleet Air Arm. So, I went into Sheffield, saw the Navy recruiting office and they sent me up to Darlington. The Commissioning Board said, “Yes, no problem.” At the Medical Board the guy said, “Don’t like your eyes. They’re not very good. One eye is not very good. We can’t accept you for flying.”

I said, “What do I do now?”

“Well, you can take your discharge from the Navy,” (because I had to enrol in the Navy as a first step) “and that’s it. You can please yourself.”

I came back home and decided I still wanted to fly, so I went to Royal Air Force recruiting and said I wanted to fly. “Yes, right. You’ll have a medical.” I went down to Cardington, joined up as aircrew, went to the aircrew receiving centre and had various medicals etc, etc. Once again, they weren’t happy to take me for pilot training because of this lazy eye, supposedly.

I started training as an observer in night fighters. They were using Bolton Paul Defiants as night fighters at that time with early radar in the back. That fell through very quickly so they said, “What are you going to do now?”

“Well, I don’t know. Basically, I am a metallurgist. I have studied etc, etc, and I am an engineer.”

“Oh well. What about transport?”

“Not really.”

“Well, we think….”

So I said, “OK” and I went to RAF Weeton, outside Blackpool, and did a course there to train as a Mechanical Transport Fitter. I came out well in that and they said “Right, we’ll put you on an instructor’s course and you will then instruct other people.” So, I did that for a while.

Next, I was posted onto the Orkneys. I was up there for about six months and then I went to a place called Bobbington, just outside Wolverhampton. I was there for a bit and I think it was from there that I was eventually posted down to Salisbury or, rather to Old Sarum and the unit down there. We were there some months running a waterproofing school. It was a little unit. We had a little wooden hut at the side of the pool and the vehicles turned up and we put them through it. If they ‘drowned’, of course we dragged them out. I suppose we were probably there three or four months. I was a Corporal, instructing on MT vehicles and maintenance and that sort of thing. I suppose that’s why I was dragged into the thing.

Beach Flight

I was in 103 Beach Flight. My commanding officer was Flight Lieutenant Binns. Some of the members, as I met them, had been in it for some time because they used to tell me some hair-raising stories about some of the training. I think they trained with the Commandos up in the Clyde.

The unit moved into a concentration area in the New Forest. We went from there to Southampton where we embarked. It was a Canadian LCI(L) [Landing Craft, Infantry (Large)] with two big ramps at either side. The ramps would be lowered, and you would go ashore in about 3′ 6″ of water or something like that and storm up the beach with all the muck and bullets flying about.

[source : Landing Craft – LCI(L) 299 – For Posterity’s Sake (forposterityssake.ca)]

It was a pretty rough crossing. It wasn’t as bad as the day before, but it was still pretty horrible. I couldn’t sleep. I suppose it was apprehension and Goodness knows what. The wheelhouse was completely covered in. The guy at the wheel took his orders from the Skipper who was up the top. I stuck my head in there and the guy at the wheel (he was a Canadian), he was as green as grass.

I said, “Are you having problems?”

“Hell, can you take this?”

“Yes.” I’d had a boat of my own and I said, “No problem, yeah.”

He said, “The Skipper will tell you the course.”

I took the wheel and this guy disappeared. I stood there with the wheel. The Skipper came on and said to steer whatever it was (I can’t remember the course) and I said, “Aye, aye Sir.”

The Skipper said, “Who the bloody hell is that down there?”

“Well, you won’t know me,” I said, “but the helmsman has been taken violently ill and I’m on the wheel.”

“Have you ever conned a boat before?”

“Yes, I’ve got one of my own.”

He said, “Alright” and that was that. I was on the wheel for most of the rest of the night.

On the Beach

I don’t really remember much of the landing itself, other than it was bloody wet! The water was up to my waist and occasionally slopping up to chest high. It was cold and I was bloody miserable! The engineers had cleared all the entanglement and whatnot on the beach and cleared a path through the mines straight up, but there was still a lot of muck flying about.

I landed in Normandy early in the morning of D-Day. That was why it was so dodgy when we went up the beach. We eventually got through this gap in the sand dunes. I got a bit of shrapnel in my tummy. We were under shellfire. I just stuck a patch on it, that’s all. I said, “Don’t worry about it. It’ll be all right.” It sort-of self-sterilised, you know, with the heat of the explosion. I never went to a dressing station, just stuck a patch on. It was a bit sore at the time, but it has never troubled me. It’s in my tummy here and if I go for an x-ray, they get very excited, “Oh, you’ve got something down there!”

“Yes, it’s a bit of shrapnel. Don’t worry about it. It’s not troubling me.”

The most disturbing part of the whole thing was going up the beach because there were so many people who were lying about in all sorts of bits and pieces all around me, who had been on mines or been shot etc, etc. The initial slaughter was pretty wicked. I was lucky. In fact, the whole unit was lucky. None of us were badly injured. Why we got away with it, I don’t know.

We had been through a briefing where they took you in and they had a wonderful table with a three-dimensional model. They showed you everything. How you go up there and arrive here and set up the DVP [Drowned Vehicle Park] there etc, etc, etc. I was amazed by this, and I think it was mainly applicable to those landing early. How the hell they had got all that information I didn’t know, but then of course you learn about it later on. I thought that was absolutely brilliant.

So, it was as we had seen it. It was like that. On the East of us was Courseulles. So, we were on the beach there. We eventually got through the sand dunes at the top and made a small sort of unit there with the DVP and settled ourselves in there.

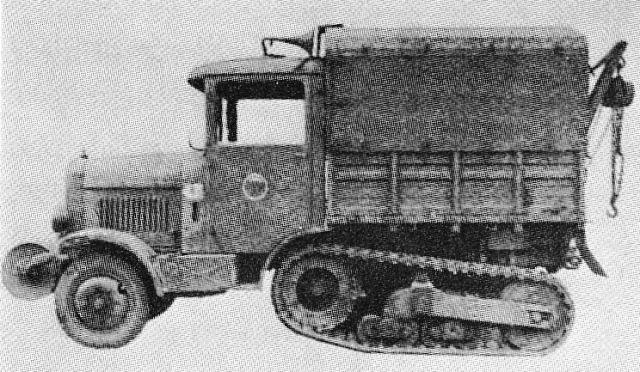

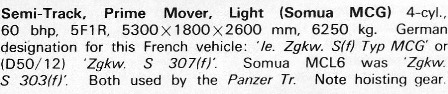

We were equipped with a Bedford QL. 4 x 4, 3-tonner. I think we had two of those. They really were not very good for wet landings. They really wouldn’t pull the skin of a rice pudding. We picked up a most wonderful vehicle. We found on the beach, a French-made SOMUA. This was a peculiar, hybrid sort of vehicle – the front half of it seemed about 1928. It was a half-track with winch back and front. Well, you couldn’t fail. It was a wonderful vehicle. We did more rescues with that than we did with the Bedfords. We commandeered the thing and said, “That’ll do for us,” and it did the bulk of our recovery work.

Basically, we were there to recover RAF vehicles that got drowned. But if there were no RAF vehicles and anything else got drowned, we would drag that ashore, whatever it was. We dragged a tank ashore and got it in the DVP. We went to take the plate off to get into the engine to dry it out and the bolts were all specially sealed. Anyway, we broke our way into the bolts and were looking at the engine and I said, “Well, I’ve seen a Merlin engine in some things, but I’ve never seen it in a tank.” It had a Merlin aero-engine in it. Just at that point some guy came up from the Army. Oh, and he went speechless. He said, “That’s on the secret list and you’re not supposed to be in there.”

“Don’t talk so bloody wet. The things drowned and we trying to get it going again for you.”

Oh dear, dear what a fuss! Anyway, we got it going again.

The worst thing was, there was a church about a mile inland and the Germans had a bloody sniper in the belfry. We all cheered when they blew the steeple down. He had really become a pest because as I say, we came up through the sand dunes onto a sort of coast road and we had a DVP there and on the seaward side was sand dunes, so this guy was looking right down at where we were. So, our problem then came from behind us. He was a bit of a pain in the neck.

You dug your own hole. I was in a slit trench with another guy who was a broad Glaswegian (I can’t remember his name) and all the troops that were coming ashore, or all the later ones, were given little blow-up lifebelts – tube sort of things. So, we got the idea that we would collect a lot of these and line the bottom of the trench with them, so that we could sleep on them. We slept in those trenches all the time. I think we came up on the surface eventually and knocked up some sort of tent accommodation or slept under the vehicles but certainly in the early days we were in slit trenches all the time. Life being somewhat uncomfortable with snipers and what have you, I didn’t manage to go to the toilet for about 10 days and then finally managed to relieve myself behind a hedge.

We came under shellfire again later on – it was probably a month or six weeks after D-Day. Everything had gone quiet as far as we were concerned. We were still doing wet landings because Arromanches weren’t getting a lot of stuff through there and we were still wanted on the beach. We weren’t carrying arms or anything like that because it was quiet. We came under shell fire again one night. They were firing down the coast. They had got our range, so we shot off to what had been a concrete gun emplacement and we slept in there overnight and came back the following morning, or the following tide, whatever it was, to do what was required.

So, that’s it. We were on the beach until, eventually, there were no wet landings coming ashore and we just wandered around for a while and then they said, “You’re going back to the UK.” So then we all went to Arromanches, dropped the vehicles off and sailed back from there. I got leave. I came home on leave but there were only a few people allowed to go on leave, the rest had to go somewhere else.

Far East

I wasn’t in the UK very long. This would be September 1944. I was posted back to this unit at Bobbington where I had been before, although by that time it was called Halfpenny Green. I wasn’t there very long when I was sent on embarkation leave. I was going abroad again. I went up to Morecambe PDC and while I was there a young, well, younger than me chap approached me and said, “I’ve been told to look out for you. I’ve been posted to this beach unit.” I said, “Where’s the rest of them.” and he said, “I don’t know I haven’t seen any of them.” I said he could hang about with me, which he did.

We sailed from the Clyde around Christmas 1944 destined for the Far East. The ship went through the Med and the Canal, of course, and I landed in Bombay. Train across India, down to Madras, ferry across to Ceylon and I was in Ceylon for six to eight months.

In Ceylon we were attached to a Maintenance Unit. We were a vehicle service unit. Vehicles came in that had various problems. we would put them all right, service them and get them ready for going out again. I think it was 145 RSU [Repair and Salvage Unit].

Suddenly I was pulled out again to report at Madras. We were in a concentration area at Madras where a force was assembling for an invasion. The unit in Ceylon had a waterproofing tank though we never put anyone through it. It seemed as though it had gone dead. But when we got to Madras there was one there, so we were running the one there for a while.

At Madras there was a whole crowd of guys that I had seen before. I had the impression, I don’t know, that the beach unit guys were scattered to the four winds after France because there was nothing lined up for them, but they picked them up again later on, when they wanted them. I never saw any of the others until I got on to Madras and they suddenly appeared from various places again.

We got called for embarkation and we were down on the dockside, ready to embark but the Bombs had been dropped and then Japan surrendered. Because of that it was everything back to where you were, sort of thing. Back to the unit in Madras, there for a few days and then back to where you came from. I went back to Ceylon and that was pretty much the end of the story really.

Eventually my number came up and I came back home- was it Blackpool or Morecambe where I got demobbed? I was given a sports-coat and trousers, and a bag. I was back in Rotheram in the January or February of 1946. It was a terrible winter. There was I, just back from the tropics. tramping through two feet of snow. It was quite a shock.