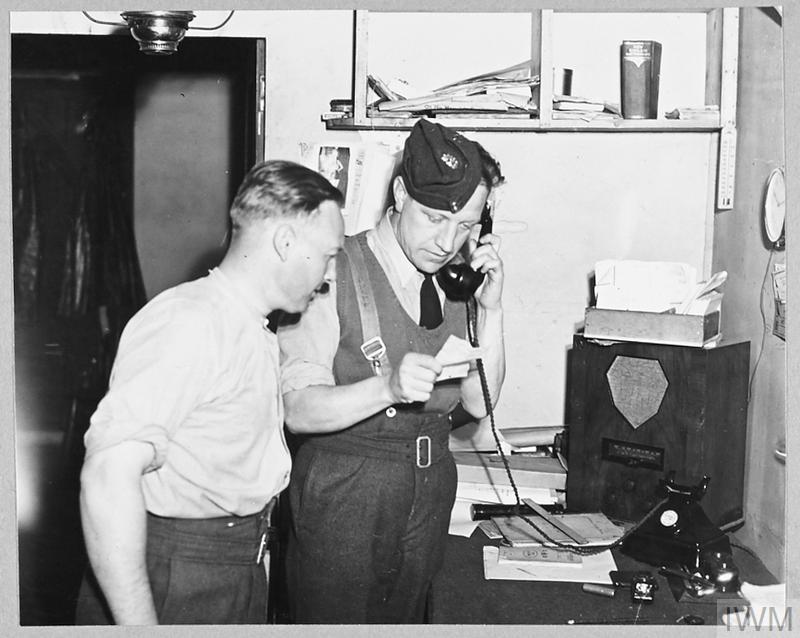

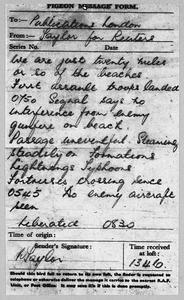

In a previous blog post, The Pigeon Connection, I wrote about the Air Information Unit attached to No. 1 R.A.F. Beach Squadron. This was led by Alan Melville, an R.A.F. Air Information Officer, accompanied by war correspondent Montague Taylor, and a cameraman from the R.A.F. Film Production Unit. Alan Melville wrote in his book:

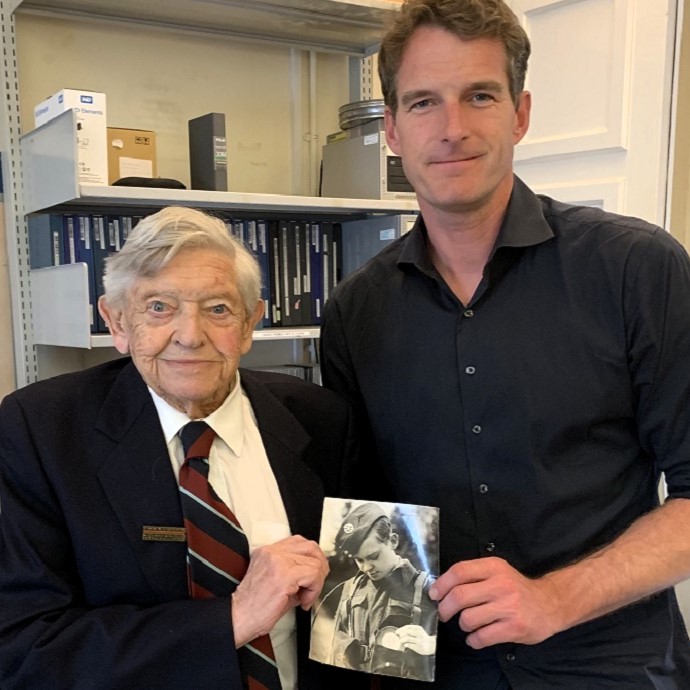

The film unit boy was the youngest looking Sergeant I had ever seen, by name Alf. He was making a pathetic attempt to grow a moustache, and spent a great deal of time stroking the thin wisps of down which he had managed to cultivate over the past few months. He was quiet, shy, and tremendously efficient.

Alan Melville, “First Tide”, Skeffington & Son, London, 1945 (page 11)

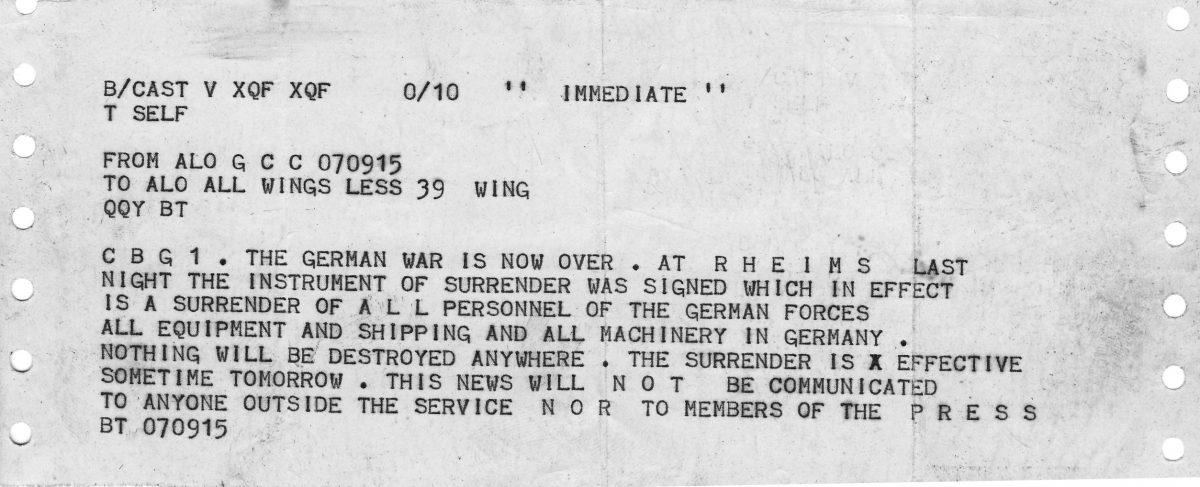

“Alf” was Sergeant Alfred Hicks. This is clear from some of the digitised film attributed to Alfred Hicks on the IWM website. This film includes shots that relate to No. 1 R.A.F. Beach Squadron and other scenes referred to in Alan Melville’s book and other accounts.

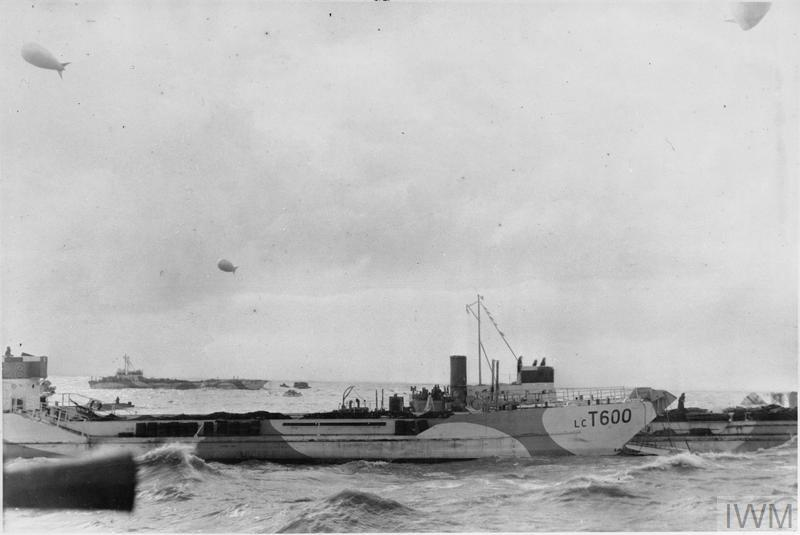

Melville describes how his party embarked on LST 302 at Portsmouth and “lay at anchor for three days while our part of the invasion fleet mustered”. They weighed anchor at 6.30pm on the 5th June and sailed for the SWORD Assault Area. They arrived off the beaches on D-Day.

We had to unload the DUKWs first: they left us two miles out and made their own way ashore. Alf went in on the first one in order to use his camera on the spot as early as possible; he waved back at us cheerily enough, but he was looking a little white.

Alan Melville, “First Tide”, Skeffington & Son, London, 1945 (page 27)

[clip from INVASION BEACHES, FOUR DAYS AFTER D-DAY [Allocated Title] | Imperial War Museums (iwm.org.uk)

After the DUKWs swam off, a rhino ferry had to be manoeuvred into position to take everything else ashore. It was some time before Melville and Montague Taylor, with their jeep, landed on the beach. After a further while in the confusion of a beach under fire, they eventually found 101 R.A.F. Beach Flight H.Q.

Alf walked into the dugout an hour after we reached it. By that time we were pretty sure that he had been killed. He was even dirtier than we were, and he sat down and accepted the mug of tea which was shoved into his hand without saying a word. But on being given a cigarette he recovered sufficiently to vent his spleen on the officer in charge of the DUKW in which he had come ashore, who had refused to stop to let him off and had swept him inland and deposited him with his camera very near the enemy lines. Alf had staggered back to the beaches as the one person who was shooting with something other than a gun, and thought he had got some rather good pictures.

Alan Melville, “First Tide”, Skeffington & Son, London, 1945 (page 32)

[Source Dan Snow meets Alfred Hicks, a cameraman who filmed D-Day | IWM Film (iwmcollections.org.uk)]