When John Hughes Fenton joined the R.A.F. in 1942 he mustered as a Ground Observer. However there was a surplus of Ground Observers and he was employed in general duties until he applied to train as a “Clerk, General Duties (Code & Cypher)”. This had the appeal of giving immediate promotion to Sergeant. After qualifying as a Cypher Sergeant in November 1943, John was based at R.A.F. North Coates. In April 1944 he was posted to No. 4 Beach Squadron.

This is his account of his Beach Squadron experiences.

Nobody at North Coates had heard of No. 4 RAF Beach Squadron, the unit named on my posting instructions. I stood whilst the clerk in the Orderly Room at North Coates searched through his directory of RAF units. Nothing!

“With a name like that, could it be one of those Combined Operations Units?” he ventured.

Strewth! Combined Operations? Me!, I thought. Though, on reflection, I had to admit to a stirring of excitement.

They sent me off to Bracknell, Berkshire, when finally they did trace my new unit. And when I got to Bracknell, guess what? No Beach Squadron! My new unit had moved on. I was fed, watered and given a bed for the night and again despatched, this time to Southampton.

I found what seemed like a sizeable chunk of the British Army encamped amidst the concealing trees at the north end of Southampton Common. Almost lost amongst this soldiery was a small group of airmen – the Headquarters of No. 4 RAF Beach Squadron.

I shared a tent on Southampton Common with my fellow NCO’s of 4 Beach Squadron HQ. They shot me a horrible line about the toughness of the Combined Operations training which they had undergone in Scotland. That only served to confirm me in the view that it was just as well I had missed it – the Second Front would be a doddle compared with Combined Ops training. I soon learned in broad terms what the function of the Beach Squadron was and where our small Signals Section played its part. That we would be landing on D Day was understood from the start; the only unresolved question was “Will we be landing first or second tide?” We were kept guessing until the last minute on that.

Every few weeks, there would be a sudden clampdown and we would all be confined to camp. We were never sure whether this was it or not. In the early days, it was evident that if this was it, then we would be setting out without half of our essential equipment. Almost daily, new equipment was issued to us, and sometimes withdrawn just as quickly. Standard items of kit such as greatcoats and rubber boots were handed in. Leather jerkins were issued. Airmen normally had a dress (tunic type) uniform, invariably known as ‘best blue’, and a battledress. We handed in our best blue in exchange for another battledress.

There was, so the grapevine said, much debate as to whether we should wear khaki battledress (with RAF badges) or wear our blue RAF battledress. It was decided that we would wear blue RAF battledress, sporting additionally (rather proudly, I have to admit) Combined Operations badges. This decision was later much regretted by our motorcycle despatch riders. The yellow dust which rose in clouds from the dry, often improvised roads in Normandy constantly enveloped everything that moved along them. Such a dusting, over a blue battledress, rendered it unnervingly like German field-grey, and our despatch riders took a very poor view of being shot at by their own side.

The new battledress issued to us on Southampton Common raised clouds of white dust when shaken. So much so, that several of us draped them over bushes overnight, in the hope that the overnight dew might mitigate that feeling of being permanently at the centre of a whirling dust storm. It was not until after the War that I read that one of the measures adopted to raise hygiene standards above those of the First World War had been to issue battledress impregnated with DDT, the newly-discovered insecticide powder, to those embarking on the Second Front. As usual, nobody had told us.

Our Wireless Operators got a new Collins marine transmitter/receiver, plus a spare, with which to familiarise themselves. We tested walkie-talkies on Southampton Common and, when we did get out of camp in the evenings, the shortage of beer ensured that our pub crawling, starting off at the Basset Arms, was a meticulously planned operation.

In camp, our leisure time was spent in watching endless American films from hard, too easily collapsible, wooden forms, under billowing marquees. And constantly we checked, rehearsed and counter-checked equipment and its uses.

For our last rehearsal (we didn’t know it to be the last, then) we participated in a mock landing on Hayling Island. Digging slit trenches on the golf course we found was hard work. Our secret, cryptographic documents were dumped under sacks in the back of our Bedford 3-tonner and left to Providence when, in the middle of the Exercise, we found a pub with some beer.

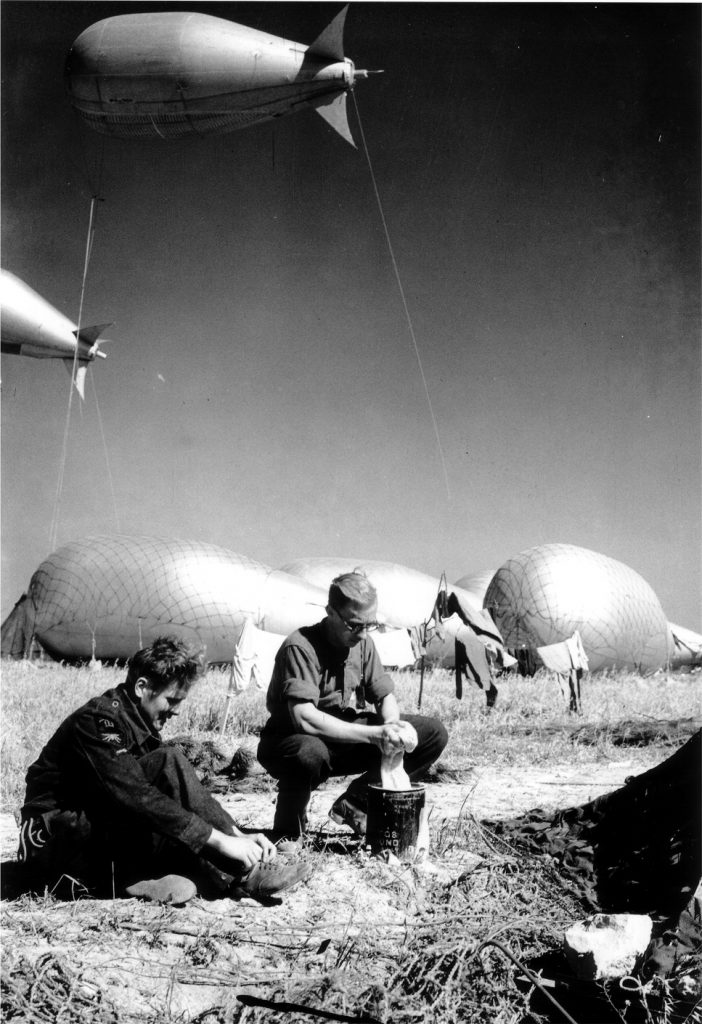

We slept under gorse bushes, but in some comfort, for an ill-wind that brought down one of the many kite-balloons flown by Landing Craft, brought us some good by providing balloon fabric which was waterproof and, when bunched-up to trap the air, buoyant.

We were lucky to collect such a find. Having spotted it come down, it was only because we so confidently asserted to our sceptical, but unsure, Navy and Army comrades-in-arms (who like us, knew a good thing when they saw it) that, representing the Royal Air Force, we were obliged to recover the balloon, that they reluctantly conceded possession.

Unexpectedly, I got seven days’ embarkation leave. Daytime, I called on my numerous relatives in West Rainton. Convivial evenings spent with my friends at the Mill Inn did nothing to impair my feeling of physical well-being. I felt full of fresh air and fitness.

Back from leave, almost immediately we moved camp to the grounds of a stately home, near Ipswich. The pace quickened. Work was more serious. We were told that we would be landing Second Tide; we had no complaints about that. More briefings, conferences of officers, waterproofing of vehicles. (Contraceptives were in great demand. What better for waterproofing jobs? When I waded ashore, at least I had a dry box of matches in my pocket.) To our considerable satisfaction, we were not allowed to wash our underclothes and hang them outside our tents in case enemy reconnaissance aircraft were aided in spotting us. New underclothes were issued. We buried the old ones.

It made sense to take every precaution, though when we made our way to the village pub, through country lanes crammed with hundreds of military vehicles, parked nose to tail, many of them still having minor adaptations made to them by drivers and mechanics, one could not but wonder how this activity could be concealed from the Germans.

We were now ordered to pack most of our kit in our kitbags, to be left in one of the Squadron’s vehicles, which would join us later. Dress was Battle Order.

The weather was hot. On Whit Sunday, the service from Durham Cathedral could be heard broadcast on our camp radios. I finished reading Siegfried Sassoon’s ‘The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston’, enjoying it. It suited my mood, I told my parents when I wrote to them on 1 June, just an hour or two before I heard that we had got our orders to move. The camp had been sealed for a week and we were informed that we were to move next day. This time we sensed the atmosphere and were fairly certain that it was not going to be another dummy run.

It was my luck to be Orderly Sergeant, so I was up at 5 am next morning, 2 June. I got all our party up on time and by 8 am, we had left the camp, part of a vast, road convoy. Nobody knew, but everybody guessed what was happening, including the magnificent housewives in the villages through which the tanks and vehicles crawled. They poured us gallons of tea and treated us so much like heroes that we almost believed it ourselves.

Among the sand dunes of a river estuary – we were at Felixstowe, someone said – on a warm summer’s evening, Army pay officers at trestle tables gave us the first confirmation of our destination. We lined up, handed over whatever English Treasury notes we had, and received in exchange crisp, newly-printed French franc notes. So, it was France!

The loading of Landing Craft seemed interminable. Vehicles and tanks had to be reversed up the steep, narrow ramps so that later they could drive straight off. Recovery vehicles stood by to help the unfortunate. Occasionally, less skilled drivers would be replaced temporarily by the more adept. Securing chains had to be fixed, and when each Landing Craft had its full load of vehicles, the personnel were taken on board. At 10 pm, I boarded an LCT, numbered 3539.

An LCT (Landing Craft Tanks) was little more than an open, steel box with a bridge, small engine-room and minimal crew accommodation at the rear, usually skippered by a Lt. RNVR. Something like a dozen vehicles could be carried. The only accommodation for troops was on top of, or underneath, the vehicles and, as each Landing Craft pulled away from the loading ramp to moor in mid-stream, grumbling, cursing ‘squaddies’ struggled to find space in which to lie or crouch.

Darkness found me as Orderly Sergeant dispensing a Navy-issue blanket, sewn to make a make-shift sleeping bag, to each ‘passenger’, stumbling along the narrow catwalk which ran the length of the ship on either side, crawling under vehicles, cursing the overloaded box we were in.

Next morning, we were issued with a printed Order of the Day, signed by our illustrious Supreme Commander ‘Ike’ then, not to be outdone, another from ‘Monty’; plus a booklet telling us how to behave ourselves in France!

Nobody told us the answer to what was uppermost in our minds. Why had we not yet sailed? Where, exactly, were we going?

For two days, we fretted, sitting on top of the trucks as the Landing Craft swung at anchor. We had self-heating tins of soup and cocoa, plenty of chocolate, and iron rations, but not much else in the way of food. A field kitchen of sorts was rigged up in the space at the front of the LCT, between the outer and inner ramps, food was acquired from some source or other, and some rough and ready meals were produced.

Sunday, 4 June, the sea was choppy and the wind strong. My face was sore with sun and wind. There were no washing facilities. At least a dozen ships nearby lost their defensive balloons in the wind. Unknown to us, D Day had been postponed for 24 hours because of adverse weather forecasts.

Next morning, at 9.10 am, we put to sea, much to everyone’s relief. By then, we would have gone anywhere and done anything, just to get off the Landing Craft. Orders were issued; tin hats and lifebelts on; boots off; day and night. I hadn’t much faith in the flimsy lifebelts but, when partially inflated and the ends pulled tightly together, they made a reasonable pillow.

The sight of the convoy was awe-inspiring. All types of Landing Craft covered the seascape. LCTs wallowed in the troughs of waves. We were sea-sick. My morning cocoa and chocolate ration wasted.

Hooting destroyers sped around, shepherding us along. Recovered from our sea-sickness, we ate from our mess-tins, then having tied string to the handles, we trailed them over the side to clean them and, in many cases belatedly discovering the strength of the sea, watched them spin away to the ocean bed, leaving just a dangling piece of string as evidence of the ocean’s deceptive power.

Not long after 10 pm, we were through the Straits of Dover, relieved but puzzled as to why the Jerry coastal batteries and/or Luftwaffe did not have a crack at us.

We curled up under the vehicles to sleep. The sea breaking over the blunt bows sent a ripple of water skimming over the steel decking on which we lay. Awakened by this, I rolled myself in my anti-gas cape and went off to sleep again. Above us, the vehicles rocked on their creaking springs and clanking holding chains.

Tuesday, 6 June dawned fine. The sea was rough. Weary of the sea and the cramped discomfort, we longed for the approach of land. Any shore would do!

The day dragged. The first troops would be ashore now and have gained a bit of ground. By God, we hoped so! We pulled on our heavy boots for the first time since embarking, and donned leather jerkins. Small pack, blanket and groundsheet, respirator, gas cape, entrenching tool, water bottle, sten gun and ammunition pouches were checked.

Large fires and intense A.A. fire could be glimpsed on the French coast. We were ordered off the vehicles – told to get underneath them, into the cover of the Landing Craft, so none of us were able to feast our eyes on the attractions ashore, now clothed in a darkness constantly torn by high explosive.

In my small pack, tucked inside my mess-tin was a 24-hour ration pack, also mug, irons (knife, fork and spoon to the uninitiated), towel and a pair of socks. Within my rolled blanket was my latest Book Club book – I think it was ‘The Gay Galliard’ – I never went anywhere without something to read. In my hip pocket was a flask, a recent present from my Dad, full of whisky.

Sergeant Hobkirk was carrying our cypher books in a small, canvas sack. As he and I sampled the contents of my flask, we agreed that as he was smaller than me, and we did not know the depth of the water in which we would land, I would take them.

It seemed as though the final run-in would never begin. Why the delay? We were late and the tide would soon turn. We were a sitting target. The bloody Naval Lieutenant had got himself lost. Engine throttled back again. Somebody said we were waiting for the OK flash from the Beachmaster’s Aldis lamp.

At last, the engine took on a more confident note and we steered a steady course…..

Drivers squeezed into their vehicles. The shackles were knocked off. Got our packs on. Sten gun in right hand. Sack containing cryptographic material in left – bizarre! Plenty of activity ashore.

Going straight ahead now – no messing. A bit of a bump and slither – must have scraped over a sandbar. Good for the Navy, they were taking us well in.

We grounded, the ramp splashed down, vehicle engines were being revved. A moment’s pause…..hope the water’s not too deep. The first man took the plunge, and then we were with him, wading…..Just two feet of water and a hundred yards to go. Me thrusting my Sten aloft….and my little sack!

Noise, confusion….where the hell did we have to make for? White tape on the ground marked a path clear of mines. Along the beach ahead was a mêlée of tracked vehicles, lorries and equipment dumps. RAF Balloon Flights unhitched kite-balloons from landing craft, attached them to jeeps, and drove off to set up their own do-it-yourself balloon barrage.

At every extra-loud explosion, or disconcertingly close whistle, the temptation to leap to cover had to be resisted. This became easier when, after succumbing to the temptation, I found that I had dived beyond the white tape into an area not checked for mines.

Our small signals group was led by a taciturn, regular Flight Sergeant. As we moved off the beach, pausing occasionally to get our bearings, he left us once or twice, and while we reflected on the noise and confusion enveloping us, endeavoured to obtain information about the objective, within 104 Beach Sub Area, we were to make for. At last, he got the information needed. To my complete astonishment and relief, we were on the right beach and shortly, on the rising ground above the beach, we reached our assembly point, only to find the rest of our unit not yet there.

Tired after four cramped days on an LCT, including two days at sea; stomachs emptied by sea-sickness and re-lined with cocoa, chocolate and the odd tot of whisky; trousers wet and boots squelching; disorientated and not a little frightened; it was clear that we would not achieve much until daylight. So, we curled up in the grass and against all the odds, including the ‘things which went bump in the night’, we slept the few hours until the early June dawn lightened the sky.

With daylight came the rest of our unit. As a precaution, we had been distributed between two landing craft. Dawn too brought intruding fighter aircraft, two being promptly shot down by ground fire, one pilot baling out. A third, I think made its escape. Later, we heard that they had been our own aircraft!

Certainly, any aircraft venturing over the beach-head was likely to meet the most formidable firepower. Shore-based Ack Ack, guns on tracked vehicles, landing craft, naval warships, merchant ships, guns of all calibres opened up at the slightest threat. It was awesome.

Our first task was to dig ourselves in. We had come up a cart-track from the beach. As the ground levelled off, there was a solitary house to the right which commanded an excellent seaward view. There, the Naval Beachmaster was already in business as evidenced by the signal lamp winking to those it favoured off-shore. Beyond the house were fields, around the perimeter of which were wooden signs bearing a stencilled skull and crossbones and the ominous words ‘Achtung Minen’. We thought good and hard about this, but there were some uncompleted trenches running across this territory and we figured there were unlikely to be any mines near them, so we could probably ignore the warning. Nevertheless, we trod a little gingerly at first.

We needed quite a big dug-out in which to install our signals equipment so, finding a convenient shell-hole, we set about enlarging it. Entrenching tools are not the most efficient means of excavation and by the end of that day, I had seven blisters on my hands.

We had dug a rectangular hole wide enough to accommodate a Wireless Operator and his set. Alongside him there was room for a Cypher Sergeant working at an improvised table. Furnishings were the crates in which the radio and portable petrol generators had been packed for transit in our 3 ton Bedford truck which had come on the other Landing Craft with the rest of our group. Seated, our heads were just below ground level so, when things got noisy, we were OK as long as we kept our heads down, and nobody dropped anything directly on top of us. To protect us from the weather, we pitched a large ridge tent over our hole. At night we encyphered our signals and transmitted them by the light of a solitary pressure-lamp.

The zig-zag of trenches dug by the Germans saved us more digging. The trenches were quite deep, and extensive enough for us to be able to choose a length as our own fox-hole. I heightened the floor with a platform of flat stones along about seven feet of the trench, so that when it rained I would not be lying in water. On top of the stones, I spread bracken, with my groundsheet over that.

I soon found that reverberations from explosions and gunfire, particularly during the nightly air-raids, caused loose soil to fall on me from the sides of the trench as I lay in it so, using my anti-gas cape and another abandoned on the beach, I draped one down each trench wall, holding them in place with stones along the top edges of the trench.

Anticipating that they might be useful, I had brought with me some blanket pins, saved from my Boy Scout camping days. With these, I converted my blanket into a much warmer sleeping bag.

Lying there in my trench, I was relatively snug, but the sight of the sky above reinforced the feeling of vulnerability already engendered by the hostile noises about me. On your stomach you never feel as exposed as on your back, so I soon got into the habit of sleeping face down; and with my steel helmet tipped over the back of my head! I did quite a bit of praying those first few weeks; there are no atheists in slit trenches.

When, after a few days, the 7th Armoured Division (The Desert Rats) came ashore near us, we slept a little more comfortably. Their tanks were waterproofed for the landing and had steel trunking forming a wide ‘chimney’ curving up from the engine exhaust and projecting vertically into the air at the rear of the tank. On gaining the beach, a small explosive charge blew off this amphibious aid. In no time at all, we cottoned-on to the fact that this abandoned military hardware could provide a roof over our head (and trench) which might keep out more than the weather.

Before starting to dig in, we had, of course, done a quick recce of our immediate surroundings. The trench system so conveniently bequeathed us by the Germans included a Light Ack Ack gun, in a sand-bagged emplacement, and a well-constructed dug-out.

We went down into this cautiously. Rifles, bayonets, other items of equipment and clothing had been abandoned. The place had just been vacated; and in a hurry! On a table in the centre of the dug-out were three boxes of cigars and a large rice cake. We were hungry. We had landed with 24 hour ration packs which were not exactly ‘cordon bleu’ living. In fact, we had not had a normal meal for several days. On the other hand, we had been warned most emphatically that we should watch out for booby traps. We eyed that rice cake very closely indeed.

“Give it a poke with a stick,” someone advised. A stick was found and the rice cake gently prodded. It moved slightly. Nothing happened. It seemed OK. Another prod. A little harder. Still OK.

“To hell with it!” a voice cried, patience exhausted, and we grabbed the cake. It was fresh and delicious. We shared it round. The cigars we savoured later.

It was there I picked up my one Normandy souvenir (it being small and portable), a standard issue German Army leather belt, the buckle inscribed ‘Gott Mit Uns’. For fifty-odd years it has lain in the bottom of my wardrobe, testimony to the uselessness of collecting such items.

Our top priority as daybreak dawned on the morning of D+1 was, of course to get operational as quickly as possible. On schedule, our equipment was eased into our dug-out, one of our petrol generators chattering healthily outside, and we were on the air. When, after a few knob-twiddling adjustments, our duty Wireless Operator tapped out our call-sign to RAF Chicksands, his signal was almost immediately acknowledged. Chicksands were reassuringly on their toes and had obviously been waiting to hear from us.

Though pre-occupied with our own tasks, when one paused and looked around from our point of vantage overlooking the beach, the sight was incredible. The beach-head was a gargantuan ant heap, pulsating with activity. At first glance, it seemed a chaotic hubbub of men and machinery but, after a few moments’ scrutiny, a pattern emerged from the mix of sea, sand, sweat and swearing.

A unique assembly of craft lay off-shore; and on-shore, for the less fortunate had been impaled on obstacles or had been disabled by gunfire. Some, undamaged, were rather too firmly grounded for their crew’s peace of mind as they waited uneasily and impatiently for a rescuing high tide. LCTs LSTs, LCIs. LCAs an alphabet of specialist craft evoked almost a train-spotting interest. Staid merchant ships, letting their barnacled keels down for once in a lifetime, nudged grooves as they listed in the sandy shallows. Small boats fussed. Clam-shell doors gaped. Derricks lowered. Men, elbows up, weapons high, waded ashore. Lorries, armoured vehicles, tanks, clattered down ramps, splashed and spluttered through swirling water.

Ships did not just line the shore. The invasion fleet was solidly three dimensional. Vessels were resolutely moving in; others backing out and turning. Ships were anchored. There were Headquarters Ships, Minesweepers, fast patrolling Destroyers and massive broadside-threatening, horizon-sitting Cruisers and Battleships.

There were few unoccupied patches of sand. Equipment dumps, slit trenches, barrage balloons, anti-aircraft guns, trailing white tape, temporary signposts, armoured bulldozers were proof that the men of the Beach Groups were about their business.

We had landed on King Sector of Gold Beach, immediately adjacent to the village of Ver-sur-Mer. The assault troops were the British 50th Northumbrian Division (who better?) whose Divisional sign TT was to become very familiar on vehicles and signposts over the months ahead; as familiar to me as their range of North East accents.

The speedy advance of the assault troops in our sector was excellent news for 4 Beach Squadron. The sound and confusion of battle was soon beyond earshot. During the day, our command of the skies was such that few but the bravest of enemy pilots attempted attack. However, at night it was a different story. It was then that the Luftwaffe concentrated its efforts on the prime target which we presented.

I kept a brief diary for a week or two in which I noted:

Thurs 8 June

Lovely morning but hell of a night. Raids most of night. Terrific AA. Didn’t feel happy though in slit trench. Stick of bombs dropped 50 yards away. Too close.

Evening. Three of us explored village. Sniped twice….scattered fast…..after lying low a couple of minutes sniped again.

Later. Visiting one of our blokes in Field Hospital – sniped again.

Fri 9 June

Went to bed 2 am after helping out Duty Cypher Sergeant….heard 4 snipers captured….cadged a Field Postcard from another unit, we haven’t got any yet. Bags of ‘fun and games’ going on now. Not so good. I’m on watch all night.

Sat 10 June

Busy. When not on duty, digging ruddy great trenches. All bed and work. Scruffy. A week since I had my clothes off. Some mail arrived – none for me. Two of our blokes got shrapnel wounds last night.

Sunday 11 June

Awakened by sound of church bells in village! Didn’t realise till then what day it was. Sent off a very scrappy letter. Busy day.

Mon 12 June

Quiet night – first time. Busy as usual. Jerry fighter/bomber tried a tip and run raid this afternoon. Dropped bombs. Scooted off. Then bang – a dozen Spits saw him off.

Tues 13 June

On duty last night. Pretty hot air raid as usual. Slept after breakfast until tea-time. Busy evening. To bed at midnight. First large batch of mail arrived together with bundle of Thursday’s newspapers. From now on we get bundle of 3 or 4 days old newspapers from the Army Post Office with our letters. One letter for me written 1 June.

Wed 14 June

Got 20 German prisoners to do some digging for us today. No mail for me. We can now say we are in France when we write.

Thurs 15 June

Hot day. One of our fellows killed by mine tonight digging trench. Very tough luck. No mail.

Fri 16 June

No mail. On duty last night. What a night. Bags of AA. Slept during day. Got a few letters written in evening.

Sat 17 June

Ocean Swell won the Derby. Too bad. One of our Sgts opened a book on the boat coming over. I had two shillings on Growing Confidence. I’ve had it…..Bags of mail at the APO….24,000 mailbags we’re told, but they can’t cope. By the time they get it sorted out, it will be out of date….The old Ramilles is knocking hell of our Jerry at the moment. (The battleship HMS Ramilles was firing over our heads.)

Sun 18 June

Not on duty until midnight so as things slackening off spent the morning in bed. Frank Gillard (BBC War correspondent) broadcasting (alongside us). In evening went on tour of exploration. Got bowl of milk and two eggs. Distributed four bars of chocolate.

Mon 19 June

On duty all night. What a lousy day! Strong wind blowing heavy rain into every corner. Eating meals in rain no joke. Two letters from home – Dick Barrass in West Africa. Frank Gillard broadcasting again.

Tues 20 June

Filthy day. Not worth writing about.

(Filmed on 20th June, some brief footage of Frank Gillard in action, as mentioned in the previous diary entries, can be seen at https://film.iwmcollections.org.uk/record/4709 )

Wed 21 June

Sea still rough. Sole topic of conversation. If this keeps up we’re going to be in Queer St.

Thurs 22 Jun

Weather improved. Still strong wind. Had trip to Bayeux this morning. Glad to see shops and civilisation again. Bought a pipe for 130 francs. Got letter from home written 12 June.

Have just seen a Fortress crash. And what a crash! Crew baled out A/C caught fire and dived – straight at us! We ran like hell. One chap looking upwards as he ran fell into trench. He’s still getting his leg pulled. Fortunately, plane turned over in the air, levelled off a little and so missed us by about a mile. It was a tense moment while it lasted. It blew up with a devil of an explosion.

Pretty hot air raid during night. Bags of shrapnel whizzing around. Unexploded shell just whizzed over our heads and hit the ground in the middle of the dugouts. It was a nasty moment. Of course now we are all laughing about our various reactions to it.

Fri 23 June

Just found out all the whistles we heard last night were from shells. Jerry was shelling the beach. No wonder we felt so windy. Scrounged a loaf of bread, four tomatoes and some tobacco from the Navy.

Sat 24 June

Had photo taken by War Correspondent. Scrounged lot of bread, sausages and oats from Navy. Will be able to live in luxury for a while.

Sun 25 June

Usual air raid last night. This time dozens of flares dropped. Looked quite pretty. After cooking breakfast spent most of day in bed. Been on duty all night.

Mon 26 June

Heavy bombardment went on all last night and this morning. Offensive started. Rained most of day and night. Bags of bailing done by us all. Pretty deadly. Went for a walk. Called in usual French house in Crépon and got two pints milk each.

Tues 27 June

Drying clothes today. Cherbourg fallen. Balloon Flight airman next to us lost eye from unexploded bomb ‘coming to life’.

Great event. Army have got cinema organised in Bayeux. Five of our unit allowed to go tonight – I’m one. Anti-climax. No film. Saw very ‘raw’ show staged by a few of the blokes.

Wed 28 June

Moved (from trenches) into house in village (of Ver-sur-Mer). Great. Very busy. (We) Senior NCO’s bagged best room as usual. Nicely organised. Built myself a bunk with planks and compo boxes. Fixed up a shelf, a towel line and a bookcase! Electric Light fixed up. Home Sweet Home.

Thurs 29 June

Hell of a day. Working dawn till dusk. Last three nights no air raids. Jerry’s slipping.

Fri 30 June

Another busy day. Managed a bath though. Had a devil of a job slinging a 30′ x 30′ tarpaulin over the (damaged) roof of our house. Air raids returned tonight.

Sat 1 July

Fine day. Took it easy for a change. Did laundry.

Mon 3 July

Saw ‘Stars in Battledress’ at Crépon. Blue as could be. Would appreciate a female show. First parcel arrived from home.

Fri 7 July

500 Lancs (and Halifaxes) dropped 2300 tons of bombs on Caen (this evening). What a sight! The most awe inspiring I’ve seen.

Sat 8 July

Monty starts push for Caen. Terrific artillery support.

Sun 9 July

Caen taken.

There my diary ended.

We had plenty to keep us busy. Cypher Sergeants and Wireless Operators worked a watch-keeping system in pairs, covering the daily 24 hours. Those not on duty, or sleeping after working all night, did the chores, the most important being the cooking.

We lived on compo rations which we collected every few days from an RASC depot. Compo rations came in wooden cases, one supplying the needs of fourteen men for a day. On producing proof of unit strength to the RASC, the appropriate number of compo cases was issued. All the food was tinned and the contents of each case similar. However, we soon learned to look for a stencilled A, B or C etc. on the packing case for that indicated whether the main meal it contained would be, for example, steak and kidney pudding (my favourite), M and V (meat and vegetables), or pork and veg. Altogether, there were about eight permutations of menu. With the main meal were such delights as tinned marmalade pudding or fruit cocktail.

We normally breakfasted on tinned sausages or tinned bacon, whilst at tea-time, there was tinned cheese, tinned jam and sometimes sardines. Margarine was, of course, tinned, and our tea came in tins ready mixed with dried milk and sugar. No question of how you like it; you took it as it came.

Also in the compo packs were cigarettes (sufficient for 7 per man per day), chocolate, boiled sweets, salt, matches and toilet paper.

Many of us saved our chocolate to give to the children and womenfolk who welcomed us as we advanced. Cigarettes, of course, became an alternative currency – quite often the preferred currency. The children very quickly became street-wise and the begging cry “Cigarette pour Papa. Chocolate pour Mama” became commonplace.

Unfortunately, we got no bread. It was more than five weeks before bread supplies became available. What we did get with our compo rations was biscuits. But what biscuits! They were as hard as rock, impossible to break with the teeth. We soaked them in water overnight, then fried them in margarine to eat at breakfast.

We had been forbidden to enter French houses or shops but, occasionally, managed to buy some milk or eggs from a French farmer or housewife. In off-duty moments, if an LST beached nearby (LCTs were more numerous but no use to us because they were too small to carry sufficient rations) we would chat up any of the crew available and often persuade them to cough up a loaf or two of bread.

With the amount of debris lying around on the beach, building a fire presented no difficulties though, if it was just a question of a quick brew-up, I had already learned the Army way to boil a can of water. Punch a few holes in an old square petrol can, or biscuit tin, and fill it with earth. Pour on petrol. Chuck a match on it and it will burn long enough to boil water for a roadside brew-up.

Water had to be transported, whether acquired from a not too distant house with a tap that was still working, or from an Army bowser. As a consequence, washing-up was perfunctory. The best way to clean dirty knives was to stick them in the ground, then wipe them on the grass.

Whilst not working, cooking or sleeping, we continued to do a good bit of digging. We were forever repairing or improving our dug-outs and trenches, trying to make them weather proof, and as bomb-proof as possible.

After a week or two, the necessity of washing our clothes became evident. I lit a fire, dumped my Army-issue khaki shirt (though that type of shirt was more green than khaki), socks and underclothes in a large, salvaged can full of water, brought it nicely to the boil, then slung my garments over a hedge to dry. For the remainder of the campaign, I was the slightly embarrassed owner of pale green underclothes.

Given an hour or two to spare, two or three of us would reconnoitre the nearby village but it was badly damaged, there were few French civilians about, and apart from getting to know the lie of the land, there was not a great deal to be gained from it.

Sometimes, I would accompany one of our drivers in our Bedford 3 tonner to pick up the rations. In common with most military transport, these vehicles had a large, circular hole, capped by a removable canvas cover, in the cab roof above the passenger’s seat. Most of the time the weather was fine and, on the slower parts of the journey, I would stand on the seat, my head and shoulders projecting above the cab surveying the scene.

The inevitable dust cloud enveloped men and machines bumping along newly bulldozed tracks. Farmyards and orchards housed a variety of military units. Grotesquely swollen, dead cows lay stiff in some of the pastures, their feet sticking in the air. Large expanses of coastal farmland lay sterile behind the threat of ‘Achtung Minen’ signs. From D+3 onwards, fighter aircraft made their landing approach to freshly levelled Somerfeld tracked (wire mesh), landing strips.

German prisoners were a familiar sight. They were shepherded up the ramps into LST’s for the return voyage to England. In the early days of the landing, we were required to do our share of guarding them before trans-shipment. I recall guarding one party, about twenty in number. To manage the prisoners better, I had got them all into a huge shell crater (resulting from the 6 am, D Day bombardment by the cruisers Belfast and Diadem of the concrete-encased Ver-sur-Mer coastal gun emplacements.)

Standing on the rim with my sten gun ready, I could keep a closer eye on them. Soon, I felt sorry for these Germans standing, sitting, crouched there – very dejected. Two could not have been more than seventeen years old. When they needed to urinate, that was no problem. Nobody was shy about that. But one put his hand up and indicated that he wanted to defecate, would I let him move away from the rest?

I gestured with my sten that he could come up and use another hole near me. Dignity hardly seems important when close by is the supreme indignity of violent death and injury, but I felt sorry for those unhappy soldiers and others who briefly passed through our hands.

When we came ashore in Normandy, our cypher equipment consisted of an easy to use, low security code which it had been planned we should discard after the first few more hectic days, plus the standard RAF Book Cypher. We never used the lower grade code. It was believed to have been compromised.

Now, when I think of our work, it is always the night watches that come more readily to mind. Our ‘office’ a hole in the ground. Two of us busily working under a small patch of light to the accompaniment of an impressive variety of noises off. Sitting on a box, with plain language messages awaiting encypherment lying on a crate in front of me, consulting my cypher book I would quickly turn the plain language into four-figure groups. We became very quick at this, for the same words were used in many of our signals. The addressees were the same.

“To Chicksand, Repeated to 1 and/or 2 Beach Squadrons, From 4 Beach Squadron.”

The figure groups for LST, LCT, aviation fuel, cannon shells, rockets were used repeatedly. So, we knew them by heart which saved looking them up.

Of course, if our encyphered signal had been transmitted in this simple form, the repetition of some of the figures would have been so obvious that the signal would have been ‘broken’ in no time. So, using equipment with settings that changed daily, we converted our messages into a second set of seemingly random four-figure groups.

All this was done by the light of a solitary storm lantern, the Wireless Operator busy alongside transmitting and receiving Morse. We knew that, if either of us stood up, our heads would be silhouetted against the lamplight so, in the early days, we were particularly conscious of snipers and, always, we felt vulnerable during the night bombing. We needed no reminding to keep our heads down.

Having to concentrate on the job helped to take one’s mind off other things. Occasionally, a transmission from one of our neighbouring Beach Squadrons would break off with a three-letter Q Code signifying “I am under enemy attack” then, later, transmission would resume. To the best of my recollection, we never went off the air, though I am sure there were occasions when the rhythm of our transmission faltered somewhat.

Twenty-two days after we landed in Normandy, we got some decent accommodation, a battle-scarred house. Just a few days earlier, fed-up with our slit trenches and having acquired an accumulation of steel trunking discarded by tanks, we had built some surface shelters. We had located them in a depression, well banked-up with soil, so that they offered some protection against blast and shrapnel. However, they were not proof against the seepage of rain. Much to our satisfaction, we acquired a damaged balloon from our RAF Balloon Flight pals, enough for each of us to cover our shelter, thereby waterproofing it. No sooner had we completed the job than we heard that we could move into this house in Ver-sur-Mer.

‘Our’ house was badly damaged. No windows or doors, a huge slice of one wall and quite a bit of the roof missing. But it was a palace to us. We were able to eat in a large room downstairs. We installed our wireless equipment and cypher books in one of the bedrooms. Four of us Senior NCO’s bagged the adjoining bedroom.

One Sergeant slept in a camp-bed that he had ‘liberated’ somewhere, another on a stretcher, and a third on the floor. I built myself a bunk using two compo boxes and some planks. I used balloon fabric as a mattress, covering it with my groundsheet. I had three blankets by then and used the inflatable rubber lifebelt, with which we were all issued for our sea voyage, as a pillow. More compo boxes for shelves and bookcase, plus a length of string to hang out my towel and it was almost like home. (Not that my Mum would have agreed!)

It was most convenient. To get to work, it was simply a matter of moving into the next room. No excuse for being late on watch. If you wanted a leak, you went straight down the stairs but instead of wending your way through the battered interior of the house you stepped through a convenient shell-hole in the gable-end, turned left into the back garden and pissed in a shell crater. At the bottom of the garden, we fixed up a bog; a luxury after three weeks of baring one’s bottom to the breeze. We even rigged up electric light, run from our accumulators, and listened to the BBC on a repaired German wireless set.

Just beyond our back garden, a cornfield separated the village from the beach. It was from this cornfield, a day or two after D Day, that many of us had suffered some sniping. After casualties amongst the troops working on the beach, the squaddies more or less said “To hell with this for a game of soldiers!”, did a systematic sweep through the field and killed four snipers. It was not anticipated that any prisoners would be taken. None were!

Everything was getting much more organised. Letters and parcels were flowing steadily. Amidst the massive newspaper and magazine coverage of the Normandy landings, three or four photographs of our unit had surfaced and our proud families sent us copies.

After five weeks, we had our first film show. The feature film was ‘So Proudly We Hail’, all about the heroism of nurses in Bataan and Corregidor; bags of air-raids and blokes having their legs off. What a choice!

Equally well meant, but a little off target, was the parcel of ‘Book Drive’ books we got. (During the War, Book Drives were held during which civilians were exhorted to donate books for the troops.) The parcel we got in Normandy contained a 1930 Motoring Guide, several forbidding-looking Sunday School prizes and a copy of Pilgrim’s Progress. Though a prolific and wide-ranging reader, I had abandoned attempts to read Pilgrim’s Progress when I was at home; it was an obvious non-starter on the Normandy beaches. There were, however, some readable books which we did appreciate.

The standard of entertainment soon improved. Within a few weeks, a huge old barn had been converted into an RAF Theatre and we saw our first overseas RAF Gang Show. It was terrific. Part of the second half was recorded and broadcast by the BBC. A few days later, George Formby and his wife, Beryl, put on another excellent show for us.

On 14 July 1944, the French in our locality were able to celebrate Bastille Day for the first time in four years. In the morning, all attired in their best, they went to church. Any Frenchman with a uniform wore it. An ex-Naval man, holding his little girl by the hand, wore his sailor’s uniform. The village postmen wore theirs. The British organised a fête with Army transport bringing in civilians from nearby villages. A Royal Marines Band and a Scottish Regiment provided music. There were races for the children, even refreshments. To mark the occasion, practically every truck, jeep or motorcycle had a spray of red, white and blue flowers tied on the front. In addition, some had ‘Vive La France’ and tricolours chalked on the sides. A festive air prevailed.

I had been into Bayeux a couple of times, though such visits were fairly low key. I saw only the exterior of the cathedral, feeling it improper to go inside carrying an automatic weapon. As for the cafés, they served neither wine nor Calvados (Normandy’s own, highly rated brandy), only ersatz coffee.

However, it was about then that the first NAAFI supplies of liquor arrived in Normandy. Officers and Senior NCO’s each got a bottle of whisky. We polished ours off in one session, quaffing it from enamel mugs. It was only after I had trotted downstairs, and out through our hole in the wall to have a leak, that events took their inevitable course. It was a moonlit night. Why was I in the shell crater? I eventually made it back into the house, up the stairs and crashed into my bed, establishing at that moment an extreme aversion to whisky which was to last for many years.

We were now shaving daily and washing our clothes once a week. We could get a reasonable sluice down from a bucket but, better still, an Army Bath Unit had been set up a few miles away and we were able to organise trips there to have hot showers. Bliss!

But, the biggest morale booster of all was the start of a regular supply of white bread.

The Normandy beach-head was now enlarged and consolidated. An increasing proportion of supplies were being landed at Mulberry Harbour. Night bombing of the beach area was still sufficient to get us out of bed sometimes, sheltering under tables on the ground floor of the house, though if on duty, we stuck it out upstairs in our wireless room.

Occasionally, brief aerial dogfights re-assured us of the RAF’s supremacy in the skies, whilst Bomber Command’s devastation of Caen marked with precision the location of our front line.

We had watched the Caen raid from the upper floor of our house. About 9.30 pm on 7 July, we saw the beginning of what seemed like an endless parade of aircraft, coming in across the Channel, flying in open formation. The leading bombers passed over us and on towards Caen. The Germans filled the sky with AA fire but the Lancasters and Halifaxes never wavered. They flew straight on, then wheeled right and began their bombing run. Bombs gone, and they wheeled right again, coming back towards us, then out over the Channel. For about half an hour, the air was thick with throbbing aircraft, one half of the sky covered with bombers proceeding to the target, the other half full of those returning. Escorting fighters weaved above and around. Not a German fighter was to be seen. From our vantage point, we could see sticks of bombs falling, and within a few minutes, huge fires.

The only RAF casualties we saw were a fighter and a bomber. The fighter pilot baled out and landed near us. The bomber was on fire and crashed harmlessly about two hundred yards from the shore. All the crew had baled out and drifted over the sea. They could not have chosen a better spot. The myriads of small craft were waiting to pull them out as they hit the water. Not one was in the water more than a minute. One landed on a boat.

As the last of the bombers was disappearing another armada darkened the sky. They did exactly as the others, the last of them turning for home as darkness was falling. By then, a huge pall of smoke was drifting towards us.

That night, an artillery barrage, supported by the heavy guns of battleships and cruisers continued to pulverise Caen. Thirty-six hours later, half of Caen was in our hands.

Towards the end of July, it was apparent that the major work of the Beach Groups was over. We speculated as to whether our unit would be disbanded, or whether we would be shipped out to the Far East to do a similar job there. We were keen to stick together, and relished our unorthodox role and avoidance of military bullshit. On the other hand, we had experienced a comparatively easy landing and might not be so lucky next time. And there were a hell’uva lot of beaches in the Far East.

To add to my own uncertainty, without notice, I was sent on detachment to assist a Signals Unit at Arromanches, about five miles away.

It was about this time that the whole expeditionary force got a new title. On first landing, we had been given an Army Post Office (APO) address. This was changed to British Western European Forces (BWEF). Now we were the British Liberation Army (BLA). And I had joined 89 Embarkation Unit, RAF, BLA.

Arromanches, with its Mulberry Harbour, was unique. In planning the invasion, the need to have available as early as possible a sheltered, undamaged, deep-water harbour was clearly foreseen. So, the bold idea of a pre-fabricated harbour, to be towed across the Channel and assembled at Arromanches, was conceived. By the time I joined 89 EU it was in full use, with consequent diminution of traffic on the beaches.

Virtually all RAF personnel and stores now landed were routed through 89 EU. Its Headquarters was located in a large town house standing in extensive grounds, though practically all I saw of it was the lodgekeeper’s cottage and a linen cupboard. The lodge was used as living quarters by the signals personnel. The linen cupboard was a tiny, narrow room with a small window, underneath which was a broad shelf (on which we worked) opposite the door. Shelves lined the walls. This was our Cypher Office.

Here our cypher activities were somewhat wider ranging than on the beaches. Quite a bit of the traffic was in machine cypher. But what machines! The exasperating, eccentric Mark III Type X machines in use had a normal typewriter keyboard but, as each letter-key was depressed using the left hand, a handle had to be cranked with the right hand to generate enough electricity to operate the printer head. There was only one printer head so, when encyphering, all that emerged on tape was the encyphered groups. There was no plain language check tape to show any mistakes. And mistakes there were in plenty, for operating the machine was not unlike patting your head with one hand whilst rubbing your stomach with the other.

They were a good bunch of blokes at 89 EU but they were really bomb-happy. They had dug a huge air-raid shelter, the entrance heavily protected with sandbags, immediately outside our living quarters. When a bombing raid started, everyone dived for the shelter. If you were slow in dropping into the entrance, someone’s feet hit you in the back. After a few nights of this, I got fed up and, when off duty, tried to ignore the off-stage noises, pulled up my blankets around my ears and stayed in my comfortable bed. For the first time for months I had got a proper bed. The springs had seen better days, but with a straw palliasse on top I was pretty snug.

The airmen I was working with had every reason for promptly going to ground when a raid started. Most of them had just recently completed a full tour of duty in Malta, experiencing the heaviest and most unremitting bombing. ‘Always take shelter’ was for them an inflexible rule, learnt in the hardest of schools.

Fortunately, sometimes I did accompany them. I wrote home on 13 August 1944.

“…..When not on duty, I’ve been building a bathroom. The building we are using has been used for several purposes recently. It was originally a large porch or hall, stuck on the end of the cottage we are living in. We converted it into an office for our section. However, one night during an air raid, we’d just left it and were doing a steady 30 mph for our slit trench when a light AA shell came through the roof and burst there instead of in the sky. Well, that wrecked it, so we are now using the framework and converting it into a bathroom…..”

At the beginning of August, we came off compo rations and on to bulk food, i.e. fresh food. A consequential effect of this was a reduction in the amount of chocolate we received. We had been accumulating so much chocolate because of its inclusion in every compo box, that many of us had been sending quite a bit home to parents and friends, whose sweets allocation in food-rationed Britain was meagre. From now on, our still ample ration would be the two bars of chocolate a week we got as our NAAFI ration.

Our overall standard of living continued to improve. I was now a regular pipe smoker and, at Arromanches, I had no problem in buying large tins of duty-free tobacco from Royal Navy sailors at bargain prices.

The weather was fine. The news was good. We were moving forward on all fronts. I got out and about when off duty, whenever I could. One afternoon, for the price of taking charge of twelve airmen and thirty-eight marines, I got a trip to a cinema in a nearby village. Other days, using the advantage that three tapes, and some good friends in our MT Section gave me, I toured the countryside on duty runs, managing to look in on 4 Beach Squadron on one occasion. Their work had really slackened off.

On such jaunts it was important to take three things. Your personal arms – in my case, sten or revolver – eyeshields from your anti-gas kit, and chewing gum. The arms were unlikely to be needed, but we had soon learned to make good use of our anti-gas eyeshields as protective goggles against the constant Normandy dust clouds. Chewing gum helped to make the dust in the mouth less noticeable.

The countryside was well wooded and green, except for the sides of the road, over-burdened by alien use. Air-strips were easily identified. Every aircraft taxi-ing down a bumpy airstrip left behind an opaque cloud, rapidly propelled by the slipstream across the surrounding countryside. The sunshine was bright, the sky blue, the sea variable but more often green.

In most fields the hay and corn had been cut. Most of the fields to some degree had been appropriated for military use but the Normandy farmers took this in their stride. Whatever we dumped in a field, be it men, machines or materials, the farmers just came and harvested what they could. One day, things would almost be hidden in a field of wheat. Next day, all would be revealed amidst the stooked corn.

Two years had now elapsed since I had joined the RAF. Next month I would be twenty-one. My parents were asking in their letters if there was anything I would especially like for my twenty-first birthday. Given my situation, I had little to suggest. What I really fancied was a spot of leave. Rumours abounded that some sort of home leave arrangement was to be set up, but they were no more than rumours.

In the harbour at Arromanches were a couple of RAF High Speed Launches. Our Signals Unit charged batteries for them. I accompanied one of our vehicles returning batteries, bumping out across the floating roadway of steel pontoon bridges to the piers where, amidst crowded cargo ships busily unloading, the sleek, powerfully-engined RAF launches were moored.

These impressive craft criss-crossed the Channel frequently and, aboard one of them, I asked the Coxswain if he would take me, assuming I could get a few days off duty. He agreed readily, but it was a harebrained scheme which never stood a chance of being realised.

The long awaited break-out from Normandy had now begun, and with it came a change in my affairs. On 24 August, Paris fell and, in what turned out to be my last letter from Normandy, I wrote briefly to my parents that I had heard that 4 Beach Squadron was shortly returning to the UK and I would return with the Squadron. We should certainly be getting leave!

I was right about returning to the UK. I was wrong about the leave. No. 4 Beach Squadron was shipped on a returning LCI (Landing Craft Infantry) to Newhaven, thence to Redhill aerodrome, Surrey. Less than three weeks later, I was back in Arromanches, this time in transit, having been posted to 83 Group Control Centre. I caught up with 83 G.C.C. outside Brussels in mid-September 1944, shortly before my 21st birthday.

John Fenton’s story is an edited version of the Normandy Beach-Head chapter of his memoirs, published privately in 1994.

After serving with 83 G.C.C. in Belgium, Holland and Germany, John returned to the U.K. to train as an officer (see his VE Day Story). He flew out to India as the war with Japan ended and served as a cypher officer in Ceylon, the Cocos-Keeling Islands and Singapore before sailing home to the U.K. at the end of 1946. After ‘demob’, he pursued a career as a civil servant but continued his involvement with the R.A.F. until January 1964, as a volunteer reserve officer, receiving the Air Efficiency Award and retaining the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

John Hughes Fenton died on 8th June 2013, aged 89.