William Sinclair MacLeod joined the R.C.A.F. in his native Canada and served with 409 Squadron, R.C.A.F. in the UK. He then qualified as a Code & Cypher Sergeant and was posted to 255 Squadron, R.A.F . He travelled to Bone, Algeria with an advanced party of 255 Squadron in November 1942. Sgt. Macleod served with 255 Squadron (a night fighter unit operating radar equipped Beaufighters) until April 1943, when he was posted to Mediterranean Air Command H.Q. in Algiers. He was keen to continue serving in a more active role and spotted a request for a Code & Cypher Sergeant to join an R.A.F. unit located in a staging compound just outside Tunis.

Joining Combined Operations

I had no idea what kind of unit it was but based on the code name used to identify it I was pretty sure it was slated for active service somewhere. I asked for and was given the posting. Little did I know what I was getting into. By various modes of transport I made my way to the staging compound and joined the unit. It was to be a small unit of thirty three consisting primarily of signals personnel. Flying Officer E. H .D. Bland, R.A.F. was to be the Officer Commanding. Once again I am to be the only Canadian (R.C.A.F.) in the unit.

After being “introduced” to my new surroundings it became clear that we were soon to embark on an exciting mission. Our wireless equipment, as well as all our code and cypher supplies and equipment were installed in a horse box type of truck. As a matter of fact we used to call it the “horse box”. While we were not officially informed of our destination it was clear that we were to go somewhere by sea. In the days following my joining this unit we prepared our truck for sea duty, i.e. equipping it so that it would operate with the engine submerged in water. This involved, among other things, attaching an upright extension to the carburetor and tail pipe, as well as waterproofing the distributor and wires and plugging any and all engine openings through which water might get into the interior of the motor. It soon became clear that I was to be given the “privilege” of driving this contraption during the upcoming mission. Many tests were performed so as to ensure that it performed according to plan.

During this period we were also engaged in stocking up with the necessary supplies to keep us going for an extended period. One very interesting sidelight, each member of our unit was at this time supplied with a distinctive shoulder badge indication that we were part of the elite special services branch – ” Combined Operations”. While we were not commandos, we wore a similar badge. As the only Canadian in the unit it was a lonely and uncertain time for me. The North African campaign was behind me but now I was to be deeply involved in a new phase of the war. Was it to be the south of France, Sicily or mainland Italy? I was twenty one years of age and far from home.

Embarkation and voyage

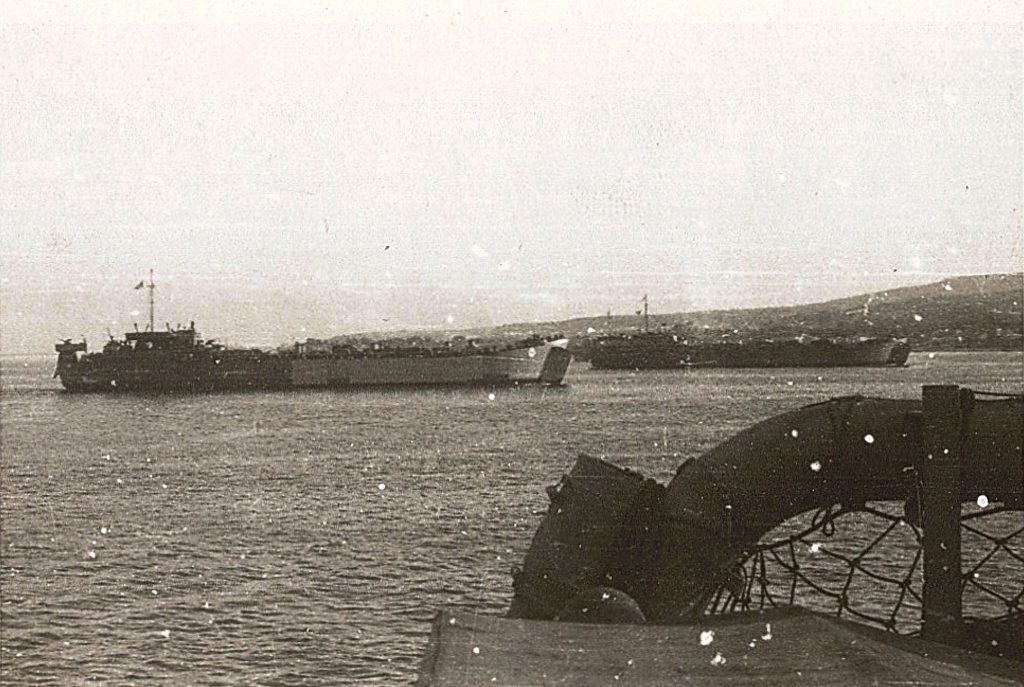

On July 3rd, 1943, our unit boarded an L.S.T in Tunis harbour. Most of the force on our vessel were army personnel together with their armored vehicles and trucks. It didn’t take the Germans long to find out something was brewing. The next day, July 4th they sent their planes over Tunis on a daylight raid. Their target was obviously the landing craft and other invasion forces which were congregating in that seaport. While they were successful in inflicting some damage in and about the port the only thing they managed to do to us was douse us with water from their bombs which fell in the water around us. Some July 4th celebration!

We remained aboard our landing craft in the harbour until setting sail on July 9th. It was while at sea we were informed of our precise mission. We were to land in Sicily during the early dawn of July 10th. Our vessel would bring us as close to the beach as possible before dropping the forward ramp over which we were to make our exit. A designated officer would direct our departure from the landing craft. Needless to say I got no sleep during the hours preceding our landing. The weather during our crossing was not as good as we would have desired. On the evening prior to our landing I recall looking out through the mist and seeing the island of Malta off to my right. What a pounding the Germans and Italians gave that little island during the early years of the war! In the darkness during our crossing to Sicily a seaman came up to me while I was standing out on deck and identified himself as a Canadian. He too was the only Canadian serving aboard this Royal Navy landing craft. He informed me that over the past two or three days he had saved up his daily tot of navy rum for a time such as this and would I like a shot of it to help calm my nerves. It was strong and hard to swallow but it warmed me up and helped calm the butterflies in the pit of my stomach. I never saw him again after that brief encounter.

Invasion of Sicily

As we approached shore there was considerable activity. Our navy was laying down quite a barrage in an effort to clear the beach and surrounding areas to assist us in our landing. There was a fair bit of enemy activity as they trained their heavy guns on our ships. German fighter planes were also attacking our ships and in particular the troops and vehicles as they hit the beaches. We had tracked vehicles helping any trucks which might get stuck in the sand after exiting their ship. I was one of those requiring help. As I exited the ship I found myself at least up to my waist in water. The engine bonnet of the truck was initially submerged but I experienced no trouble until I hit the dry sand. There I got stuck. While it only took a moment or two for them to hook up a tow and get me up onto solid ground it seemed like ages. I can assure you it was not a comfortable place to be stuck. During the landing I also watched our planes bomb sites about three hundred yards from the beach. We could actually see the bombs leaving the aircraft and falling on their target.

Our initial objective was to set up our communications network as quickly as possible. Accordingly we set up shop in an orange grove about three hundred yards inland. By this time our army had moved fairly quickly inland and it was mainly attacks by fighter aircraft that we experienced during the remaining daylight hours of Day 1. A very different situation was to develop once the sun had set.

By nightfall the weather had deteriorated but not enough to prevent enemy aircraft attacking our landing positions along the coast. Our army units had numerous anti-aircraft guns deployed all along the coast and as enemy aircraft came in to bomb and strafe our positions they received quite a warm welcome. Unfortunately at this precise time allied aircraft loaded with airborne troops approached the coast from North Africa towing gliders also loaded with airborne troops. Our anti-aircraft units were not aware that reinforcements in the form of airborne troops were coming in over our position and, with an enemy air attack in progress, a disaster of great magnitude occurred. As these slow low flying planes, towing fully loaded gliders, approached the coast, our anti – aircraft batteries opened fire, believing they were another wave of enemy planes coming in for another attack. Pilots, not knowing what was going on, cut their gliders loose resulting in a number of them crashing into the sea or on land short of their intended destination. One glider came down in our orange grove, not far from where we were located, killing all twenty-eight American troops. It was not a good night.

As our troops moved inland airbases were captured so we moved our base of operations to these sites. All in all the Sicilian operation was of short duration. By late August we were located at a marshalling yard just outside Catania. There we were within sight of Mt. Etna. A substantial part of the invasion force was assembled here as our Army, Navy and Air Force brass prepared for the next step, the invasion of Italy.

Invasion of Italy

During the last days of August our forces boarded ships of all description for the long awaited invasion of the continent of Europe. I do not recall the hour of our departure from Catania but it was during the night of September 2nd or the very early hours of September 3rd for it was during the hours before dawn that we sailed through the Strait of Messina with our long range guns in Sicily and our naval escort blasting the shoreline in the Reggio di Calabria area with everything we had. Our guns on the Sicily side were firing directly over our flotilla. It was indeed a wild and scary sight as we headed in, just as dawn was starting to break. We had no real understanding as to what we were going to face. We simply hoped for the best and planned for the worst. As it turned out the initial enemy opposition was much lighter than we anticipated.

My role on our entry into Italy was more or less identical to what I experienced during the landing in Sicily. I drove the same vehicle and traveled on the same type of landing craft. This time I didn’t get stuck in the sand. The initial forces to go ashore laid down a wire mesh on the beach so that our vehicles could cross the sand without too much difficulty. Good thinking.

Just after landing at Reggio di Calabria an Italian soldier surrendered to our unit. He spoke quite acceptable English and indicated that he wished to join our unit and fight on our side. This of course was not possible but it was decided by “someone” that he tag along (as a prisoner not yet turned over to the military police) and be our interpreter and general scrounger. He turned out to be a very valuable addition to our unit. He worked in our mess and scoured the countryside for fresh fruits, vegetables, turkeys, wines, etc. He was much more effective in this role than any of our airmen. I do not recall his name but he remained with our unit until we moved to Corsica.

(He and two of the others are posing in what appear to be ‘captured’ Italian hats)

When the work of 33 Beach Brick R.A.F. Component was finished, Sgt. MacLeod’s signals section moved to Naples and then worked at Bari before transferring, in November 1943, to No. 51 Repair and Salvage Unit at Foggia. In June 1944 they went to Corsica with H.Q. 322 Wing but in July Sgt. MacLeod was moved to the U.K. and he returned to Canada in November 1944.

These extracts from the memoirs of the late W. Sinclair MacLeod, and the photographs, are included with the kind permission of his family.